“How do you measure a military footprint?” Six years ago Josh Begley posed this question for his empire.is project, which used satellite imagery and the 2013 Base Structure Report to visualize the U.S. military’s presence around the world. The 2016 article James Walker and I wrote for Geopolitics, “Tracing the U.S. military’s presence in Africa,” can be read, in part, as a methodological exploration of the potential utility of piecing together contracting data to limn the U.S. military’s overseas footprint. We were especially interested in this approach in contexts where transparency is lacking, as is the case with military activities and sites in Africa. CENTCOM, for example, has offered quarterly updates on contractor personnel in Iraq, Afghanistan and the rest of its AOR for over a decade now. It also provides regular updates on the number of troops in the region. No such information is provided by AFRICOM, which is perhaps the least forthcoming of the geographic combatant commands.

Military footprints, of course, are never static. The U.S. military constantly shifts resources, personnel and equipment across the world, setting up and shuttering logistics nodes, bases and forward operating locations as priorities and resources fluctuate. Tracing these changes is perhaps the most difficult challenge when it comes to getting traction on the military’s evolving global presence. So how can one do this without information about troop or contractor levels, as in AFRICOM’s AOR?

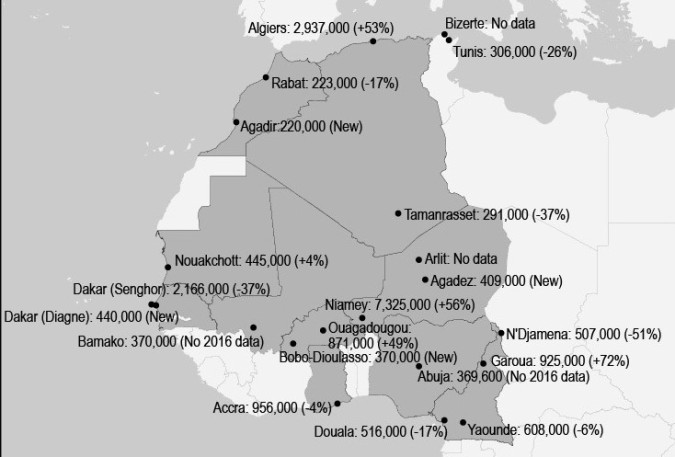

One potentially useful proxy is fuel contracts. This week, for instance, DLA posted a solicitation for planned JA-1 jet fuel purchases in Africa from fall 2019 to fall 2023. If you compare the locations and amounts of fuel purchases from this solicitation with the previous one in 2016 you can get a rough sense of changes in operational sites and tempos. (Actually, one could go back further using the 2010 and 2013 solicitations too, but I’m just focusing on differences between 2016 and 2019 here). I’ve done some basic back of the envelope work toward this end with this map of JA-1 fuel demands for logistics hubs, CSLs, drone facilities and bases that support counter-terrorism operations in North and West Africa, and the Sahel, based on this new solicitation. It provides information on total amounts of fuel (in gallons, rounded to the nearest thousand) and the percentage increase or decrease this represents in yearly demand at these sites compared to 2016.[1]

So what can we learn about the U.S. military’s footprint in this part of the world from this exercise? A few things jump out to me. First, yearly jet fuel demand in the region has increased roughly 27% since 2016, which suggests a rather significant rise in the intensity of military operations during this period. Given the noisiness of the data this increase should be considered an approximation. For example, neither Bamako nor Abuja were included in the 2016 solicitation, which is likely an oversight, given they were part of the 2010, 2013 and 2019 iterations. Similarly, the 2019 solicitation doesn’t include Arlit (a key SOF base in Niger) or Sidi Ahmed airbase in Bizerte (a drone site in Tunisia), possibly because neither are officially recognized by AFRICOM (though both show up in various contracting documents).[2]

Second, almost half the increase in fuel consumption is driven by operational demands at Niamey (+56%). Niamey is currently the most important logistics hub and drone base in the region for the U.S. military, which is reflected in the fact that it alone represents more than a third of total fuel demand. Not coincidentally, the largest increase by percentage in fuel demand (+72%) is another drone facility, Garoua. I suspect that the massive drone base being built in Agadez will surpass Garoua—and most other sites on the map—in fuel consumption by the time the next solicitation is posted in 2023.

Third, the 2019 solicitation contains four new sites requiring jet fuel in the region: 1) the aforementioned drone base at Agadez, 2) the newly completed Blaise Diagne International Airport in Dakar, which is replacing some of the traffic previously routed through Dakar’s old international airport, Leopold Sedar Senghor, 3) Agadir, which may be the site of a new CSL or SP-MAGTF-CR-AF base, and 4) Bobo-Dioulasso in Burkina Faso, which I am unfamiliar with.

Finally, fuel demand has exploded in Algiers (+53%) over the past three years, making it the second largest site in volume in the region after Niamey. I’d be interested to know more about what’s driving this shift. Is this simply a matter of Algiers’ increasing importance as a logistics hub, or does it signal something else, like a new, unacknowledged, site for drone operations? Whatever the reason, growing political unrest in the country may impact operations at this location in the future.

[1] I should note, perhaps, that I consider it most useful to treat these solicitations as approximations of the state of play during the time they are released their rather than representations of future plans, or forecasts, as DLA fuel contracts are flexible and can be—and often are—amended to reflect changes in demand. Therefore, this new solicitation not only doesn’t capture future fuel consumption (and operational activity) at an under-construction site such as Agadez, it also likely doesn’t reflect the current administration’s goal of reducing troop levels in Africa (which the military appears to be dragging its feet on as much as possible). Thanks goes to Matt Zebrowski at UCLA for putting together this map.

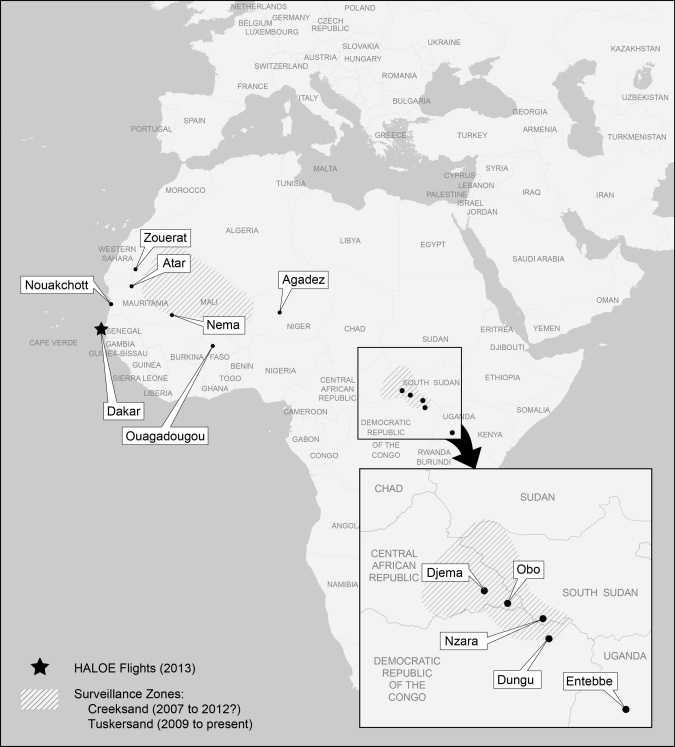

[2] Also absent are a number of contingency locations in the region identified by Nick Turse, based on 2015 AFRICOM strategic posture documents—though these sites may no longer be in use.